Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

I used to get a bit miffed whenever I heard people say that films, and especially film adaptations, stunt people’s imagination. The argument went: if you read a book, you imagine what people look and sound like, but then you watch the movie of the book and your imagination gets fixed: Alan Grant looks like Sam Neill, Annie Wilkes is the spitting image of Kathy Bates, Michael Corleone could easily be mistaken for a young Al Pacino. No more freedom of the imagination, no more imagination: you read the lines, and you see and hear the actor who made the role famous on the big screen.

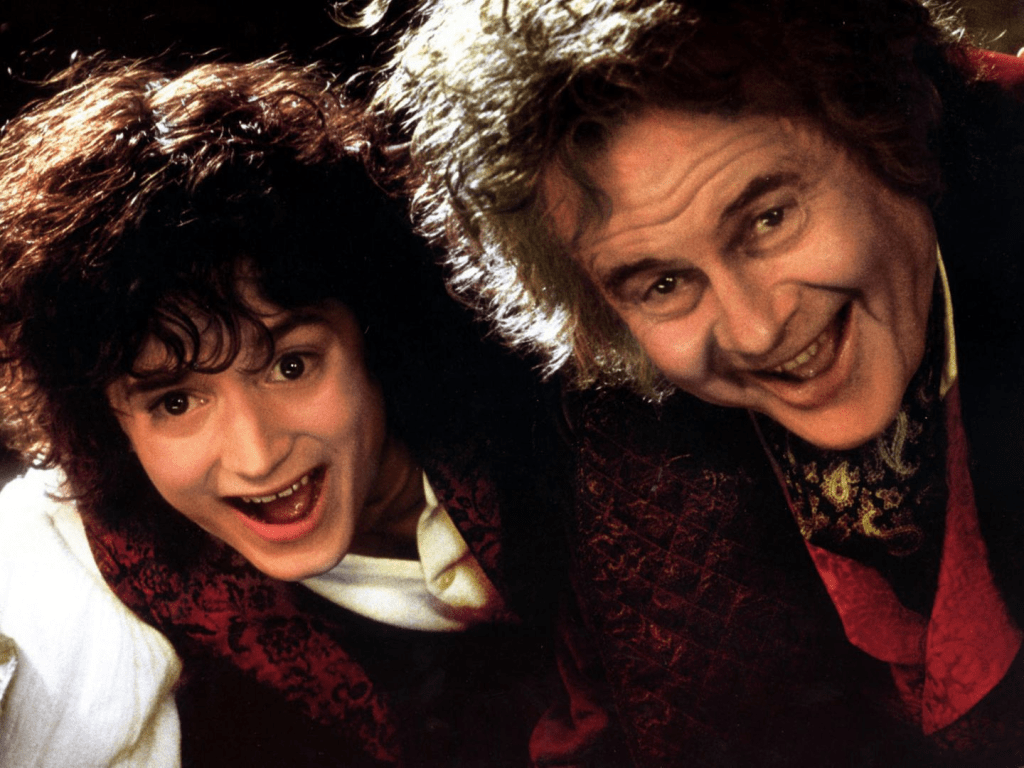

The thing is, I understand the argument. I must have read The Lord of the Rings at least half a dozen times by the time Peter Jackson’s adaptation came around – and ever since watching the films, Aragorn looks like Viggo Mortensen in my head, Galadriel like Cate Blanchett. The same is even true for the characters where I am very well aware of the differences between the novel and the film: Tolkien’s hobbits are round-faced and stout, attributes that no one would ever apply to the eternal boy Elijah Wood, and most definitely not to Wood circa 2001-2003.

The difference is even more pronounced in other adaptations: I’ve been re-reading Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies, the sequel to Wolf Hall, both of which were adapted by the BBC into the first series of Wolf Hall. In the novel, Mantel describes Cromwell as having a “labourer’s” body that is “running to fat”, which also reflects his portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger. In the series, Cromwell is played by Mark Rylance. In many ways, it’s obviously the same character, but visually the Cromwell from the novel couldn’t be much more different from Rylance’s melancholy, almost wispy Cromwell. Nonetheless, even as I was reading the words “running to fat”, I was imagining Mark Rylance, I was hearing Mark Rylance’s voice. (It is likely that Leo McKern’s Cromwell in the 1966 film A Man for All Seasons was closer physically to the actual historical character, and McKern’s performance was solid, but it nonetheless hasn’t overwritten Rylance in my mental image of Cromwell.)

So, wouldn’t that support the original argument, the one that irritated me, that films and TV series adapting books restrict our imagination? Well, yes and no. Most of us are visually conditioned, and seeing a character on screen, unless the adaptation is just plain bad, will have an impact on our imaginations. Elfin Elijah Wood is that stout, round-faced Frodo Baggins, fine-featured Mark Rylance is Thomas Cromwell, and if his body is “running to fat”, it’s highly sublimated fat, and Mantel’s Cromwell was clearly a slim Mark Rylance on the inside. The adaptations just brought out the essential Frodoness, the essential Cromwellesque physique, that’s implicit in the books, right? No, there’s no doubt that a good, engaging adaptation in a visual medium inscribes itself in our synapses, and when the appearances of characters differ from what we read in the original stories, either our imaginations fight these false images or they give up and accept that that’s what these characters look like. The latter is much more likely, I find.

Sometimes we’re lucky and there are multiple good visual adaptations of literary characters. Take Wolf Hall‘s example of charming, monstrous Henry Tudor: when I think of good old ‘Enry the Eighth, I think of Damien Lewis’ memorable performance in the BBC adaptation – but not only. I also think of Robert Shaw in A Man for All Seasons, because, well, Robert Shaw. In my head, Thomas Harris’ gourmet psychoanalyst with a penchant for eating the rude looks like Anthony Hopkins, but also like Brian Cox and Mads Mikkelsen, and when I read Red Dragon or The Silence of the Lambs, it could be any of these three very different depictions that pop into my head – or an entirely different-looking character.

The thing is: when I read, what happens in my head isn’t visual in most cases, at least not first and foremost. When I read The Lord of the Rings, I didn’t have a fully formed Fellowship of the Ring in my head by the end of it. The words Tolkien used to describe his characters remained words in my head, abstract and fluid: I could have described Frodo & Co after my many readings, but my brain doesn’t do fan castings. In many ways, it is the abstractness, the openness to interpretation, that appeals to me about reading fiction: it is not concrete faces and bodies and voices that I see and hear in my imagination when I read, it’s the many possibilities of what these nouns and adjectives and adverbs could become.

This possibility space, which appeals to me more than boiling it down into something much more concrete, and possibly wearing the face of an actor I know (how appropriate an image, especially in the case of Silence of the Lambs‘ Hannibal Lecter!), is indeed reduced by adapting the material into an audiovisual format. Reading The Lord of the Rings gave me a rich idea of Frodo and Sam and Gollum, watching the films gave me a singular, clear image of what they look like. At the same time: where screen adaptations are concrete in terms of appearances, novels often fill in spaces that films and TV series can leave much more blank – and that’s where my annoyance with the notion that adaptations atrophy our imaginations. So much writing gives us a more concrete insight into the thoughts and feelings of characters; omniscient narrators and interior monologues tell us what is going on inside these fictional beings. Watching an actor’s face, even if that face is much more concrete and, well, literal than the descriptions in a literary text, leaves emotions implicit: is Cromwell angry? Disappointed? Scared? A combination of these three, and more beyond? How aware is he of what he is feeling? Whereas a novel will often tell you these things more explicitly. All these media and forms of expression make some things concrete and leave others open to interpretation: the difference between the media lies in where the blanks are that we, the audience, get to fill in. Rylance’s Cromwell doesn’t leave up less to the imagination than Mantel’s, just different things – and in the best cases, the interplay between different takes, in different media, using different means, can be fascinating. Watching the BBC’s Wolf Hall and then reading (or, in my case, re-reading) the books allows me to think about the effects of casting an almost wispy Mark Rylance as a stocky, heavy-set Thomas Cromwell: what does the depiction change about the character, beyond mere appearance, and to what extent are the literary and the audiovisual depictions still very much the same character, in spite of the striking differences in appearance?

All of which also makes me think about adaptations in audio format, such as the BBC version of The Lord of the Rings that Alan has written about twice now. Radio series and audiobooks obviously don’t have the visual component, but they give these characters very concrete voices: does the Frodo in Alan’s head sound like Ian Holm or like Elijah Wood? (And who does Alan’s Bilbo sound like: John Le Mesurier or, confusingly, Ian Holm?) Is his Samwell Gamgee endowed with the voice of a young Bill Nighy? And, in the case of audio adaptations such as The Lord of the Rings, you have both the concrete, specific voices of the actors and the narration of characters’ thoughts and feelings. Are voices, sound effects and ambient sound more conducive to letting us imagine fictional worlds and characters? Which parts of the imagination do audio interpretations stimulate, and which parts do they supersede? And, generally, how does sound work on our imagination?