Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

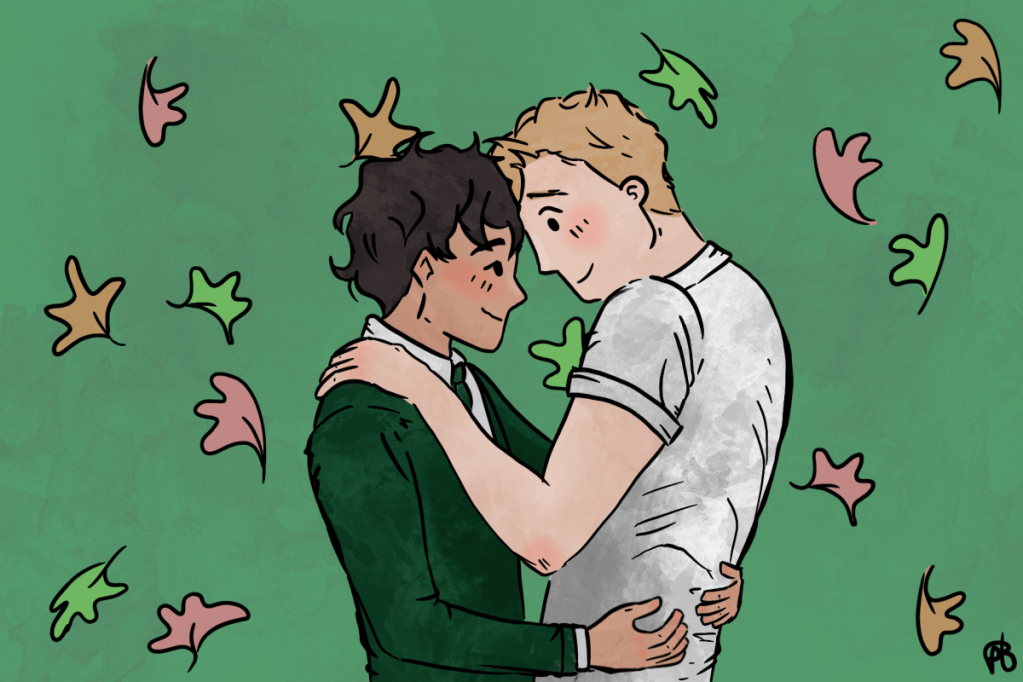

When Nick and Charlie touch, little squiggly cartoon flashes of electricity appear around them and you can literally feel the sparkles going off between them in the air. What seems just like an original reference to its graphic novel source material, Alice Oseman‘s Heartstopper series, proves to be symbolic for the runaway success this Netflix show has enjoyed far beyond the queer community: its truly feel-good approach is heartstoppingly essential for the present moment.

For decades now, queer love stories , despite real progress in representation of LGBTQ+ characters on film, TV and increasingly streaming, always depended on one key ingredient: there needed to be drama. Once gay and lesbian characters were no longer misfits, villains or comic relief (see post #26 in this series) and the AIDS pandemic no longer relegated them to tragic victims or perpetrators of seemingly self-inflicted illness or death, their path to positive and main role representation has steadily broadened and improved. Yet there always was the tragic trope of impossible love, violent bullies and intolerant societies just round the corner, and watching queer cinema often ended in the frustrating realisation that, with the increase of authoritarian tendencies, social echo chambers and right-wing manospheres, love stories between queer characters would always end up at least potentially tragic, frail or secret.

Heartstopper refreshingly turned the page on all these clichés. Of course, there are characters struggling to come out, especially in the world of high school sports leagues of Nick, and bullies haunt the other protagonist Charlie’s nightmares initially. Yet their discovery of mutual feelings for each other carries such a positive force that it puts their relationship squarely at the centre of things. It’s not the challenges of the outside world that matter, it’s rather whether they find the courage and strength to really live their love fully and loudly. It’s a surprising shift away from a potentially hostile environment to a heartwarming and self-asserting internal struggle for them individually and together. They are joined by supporting characters, their best friends mostly, who join them in similar struggles of self-confidence and self-assertion. In all of this, the drama never feels forced or for sensationalist effect only. It provides a blueprint for how to cope even if the outside odds might seem impossible.

One of my best friends recommended the first season to me during the worst of the COVID pandemic and lockdown period, and I remember how good it felt especially during that particular time. Maybe the focus on internal struggles and resolution landed on particularly fertile ground then. However, the reach far beyond queer audiences that the show has found in the meantime speaks of a much wider effect. Not only have its characters and the stars who play them caught on with Gen Z zeitgeist, they continue to reverberate in media spaces and in other roles. Just think of Joe Locke as Charlie, who has gone on to star in Marvel’s Agatha All Along (described by Alan last week), or Kit Connor as Nick, who had already established himself prior to Heartstopper in smaller roles in Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018) and the Elton John biopic Rocketman (2019) and has since become the poster boy of an entire generation, with Alex Garland’s Warfare and a main voiceover role in animated The Wild Robot as proof he might soon be an even more bankable star.

They are supported by both a young and established supporting cast, especially William Gao as Charlie’s best friend Tao, Yasmin Finney as Tao’s love interest Elle, and Sebastian Croft as Charlie’s initial bully/fling Ben. Olivia Colman wonderfully supports too few key scenes as Nick’s mom, while Stephen Fry as Headmaster Barnes offers some warm comic relief. In the third and final season, heartthrob Jonathan Bailey (of Bridgerton, Wicked and Jurassic Park: Rebirth fame) shows up as pretty much himself. They all make for a talented ensemble who help or hinder Charlie and Nick on their way.

After three successful seasons that have adapted most of the existing graphic novels, Netflix has announced one final feature film version to bring the show to a close. As with similar high school-age successes like Stranger Things (2016-2025) and Sex Education (2019-2023), their supposedly teenage stars are fast becoming older. Heartstopper might also escape the fate of some of these in not outstaying its welcome. Yet what a welcome it has been, being something truly heartwarming in the seemingly cold-hearted context which it was released into.

It’s noteworthy that its success to me is also how it feels both self-assuring and realistic, how its characters navigate their challenges with compassion, even for their skeptics and haters. It’s also a representation not only of a wishful better world but also of the reality that many live in today that does not feel as hostile or hopeless on an everyday basis as world news and grim predictions might suggest, but where real people still might have a wide range of human tools at their disposal. Besides empathy and compassion, they also include everything the lovable Heartstopper characters and story arcs have amply on display.

At the beginning of 2026, a new even stronger phenomenon of a queer love story catching everybody’s attention reminds me a lot of what Heartstopper laid the groundwork for: Heated Rivalry, the Canadian-produced hit series about two hockey players falling in love, might put the onus much more on the sexual chemistry of its male leads, but the fact that the show has gone viral with especially straight women (the Guardian just discussed this quite incredible fan phenomenon this week) is a sign that representation perception of queer love holds power far beyond formerly closeted communities: especially women seem to see in it sex-positive and ideal forms of equality between partners and the type of love relationships they desire in the real world. A world often characterised by gender conflict or alienation, by young men struggling to connect romantically (see another Netflix hit show, Adolescence, for an understanding of the devastating incel phenomenon) and by young women increasingly concluding that they have to make the world a better place on their own. Seeing queer characters love each other so beautifully as in Heartstopper and Heated Rivalry, for example, seems to have become the hope of their worlds.

Maybe just as songwriter Burt Bacharach and lyricist Hal David found out after the harsh realities and seminal changes of the late ’60s, what the world needs now is love, sweet love.