Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

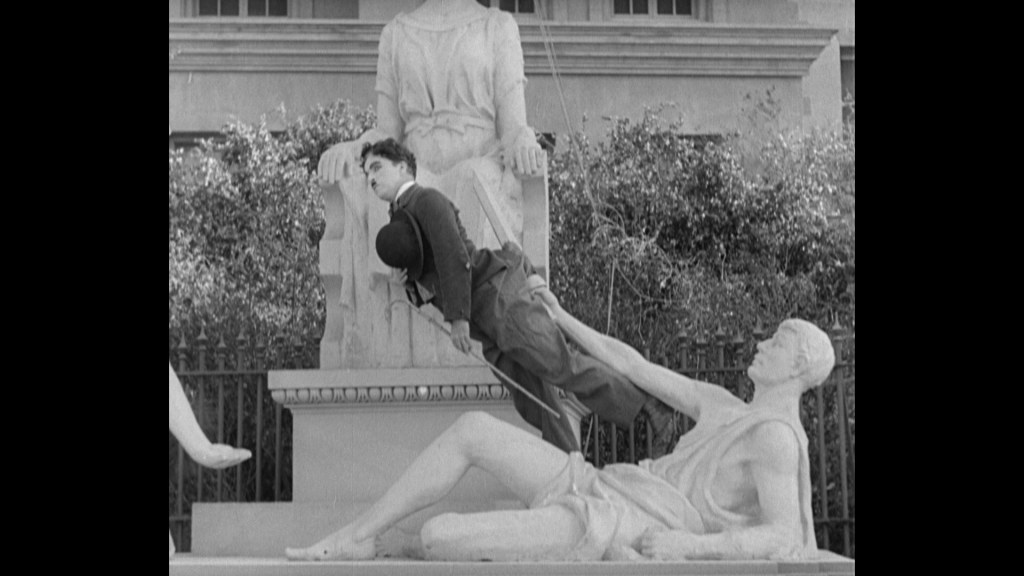

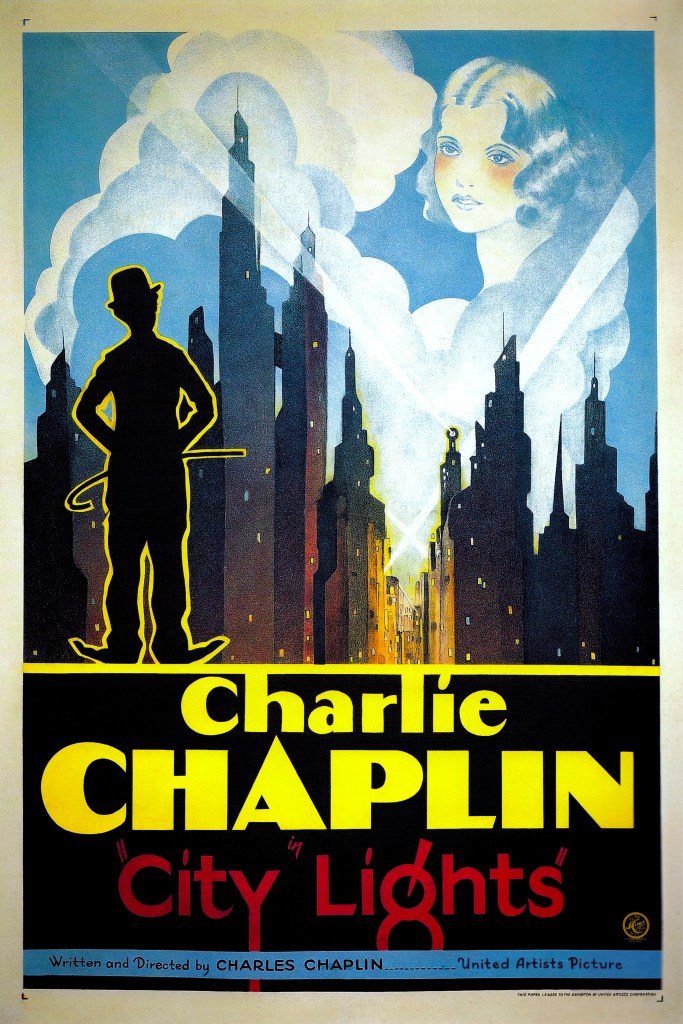

In our modern minds, the end of the silent era is sometimes imagined as if it happened with a bang. The advent of sound, and boom. The silent era ends. This is of course not the way it came about: silents and sound films existed side by side for quite some time. However, when Chaplin made the silent City Lights, the movies were already deep into the era of sound. And by the time it was finished, silents had generally gone out of fashion. The opening of the film has a little joke that is a hat tip to this (very deliberate) choice. It opens with the unveiling of a statue, with speeches by town officials, but the only sounds coming out of their mouths are quacks from a kazoo. When the statue is revealed, asleep in its stony arms is the Tramp, Chaplin’s iconic character.

“If,” Ebert writes in his movie review and summary of the film, “only one of Charles Chaplin’s films could be preserved, City Lights would come the closest to representing all the different notes of his genius.” I agree with this assessment. Even though, in contrast to other films we risk losing forever, Chaplin’s films run very little risk of being passed over for preservation, or destroyed by anyone but Chaplin himself (who did so relentlessly), City Lights features the best elements of the Tramp canon. It also has a cohesion that is absent in his earlier works, notably in his work for Mutual Film Corporation, for example. His earlier films can be seen as a series of gags, sometimes looking for logic. City Lights, in contrast, is driven by plot and emotion.

It is not too much of a stretch to think that modern audiences will have an image of this film in their minds, but may never have actually seen it from beginning to end. It is, truthfully, a sentimental film. Deliberately old-fashioned, even for its own time. But the best of its comedy feels so fresh, it never tips towards the cloying. Famous scenes include a boxing match in which the Tramp uses the referee as a shield against his opponent. And, a favorite of mine, where he is at a club and an intense dance number is performed. The poor Tramp misinterprets it as real conflict, a tormentor manhandling a lady, and attempts, valiantly but superfluously, to intervene. Another classic is the Tramp scrutinising a statuette of a nude in a shop window, walking backwards and forwards as he considers it. All the while the trapdoor of a freight-elevator opens and closes behind him, while the Tramp, oblivious, keeps somehow failing to fall into the shaft.

The film was honed and polished and buffed, to such an extent it’s almost miraculous how it retains any freshness at all. The shooting of the final scene alone took six days, and it still feels spontaneous. But it is very much choreographed and perfected to a tee. Apparently, just to give an idea, 314’256 feet of film were shot, of which only 8’093 feet made it into the film. Whether this factoid is apocryphal or not, it gives an insight into the efforts expended in getting the film made according to Chaplin’s exacting standards. Chaplin even composed the score himself. Well, mostly. In actuality, Chaplin hired arranger Arthur Johnson to faithfully write down what he had in mind, and the lovely flower girl leitmotif La Violetera later got him embroiled in a lawsuit, which he lost, for failing to credit its actual composer, José Padilla. The sound effects, however, are hilarious, incredibly creative, and I have no doubt they’re his idea. During a party scene, the Tramp accidentally swallows a whistle. An absolutely hilarious sequence ensues, in which he inadvertantly manages to lure all the dogs in the neigbourhood to gather around him.

The flower girl herself, Virginia Cherrill, was chosen when screen tests with nearly 20 actresses left Chaplin unsatisfied. The tale of how she was cast is a very Hollywood one. The story goes he met her at a boxing match, while she was visiting LA. He decided she would do, apparently due to her extreme near-sightedness which gave her the ‘look’ he wanted, and cast her. Chaplin himself would later claim that she approached him for a part, heavily implying it was of course he who molded her, but even Chaplin had to concede that they had, in fact, “met before”.

Their working relationship was not a happy one. Chaplin was known to run his cast ragged. And when Cherrill bristled, he belittled her, and ultimately fired her. Cherrill, as well as the rest of the cast, were expected to show up to the studio and wait around until Chaplin showed up. For hours, sometimes days, on end. She was bored, Cherrill would recount much later. She would read books, knit, do needlepoint. But when Chaplin did show up, it would be endless takes, all seemingly exactly the same. She would remark half-mischievously in the later interview: “Charlie was … a God. You forget, everyone forgets, that in this studio he was the only person whose opinion mattered in any way”.** Of the 534 days of shooting, a whopping 368 days were marked as “idle”. He even stubbornly reshot the famous final scene with Georgia Hale. She would later insist she had incredible rapport wit Chaplin. But by that time, he had too much invested in the film to redo the whole thing. So he rehired Cherrill and she, cannily, agreed only after he promised her a raise. The footage of the scene with Hale survives, and she’s fine in it.** But for all of Chaplin’s churlish criticism, Cherrill is exquisite, as even Chaplin would eventually concede. Cherrill would continue her career in a subdued way afterwards, but retired from acting early: she married a count and lived to be 88. She’d maintain that this early end to her career was because she was “no great shakes” as an actress, but as she had never really gone all-out to become one (she’d rejected an offer by Ziegfeld early in her career), she may have just been content to fade from the limelight. And, as she already moved amongst high society, she could even call the fabulous Marion Davies a friend, it’s not difficult to understand why that might have seemed a more attractive option to her, than to be at the whims of fickle directors.

Against the odds, City Lights was a howling success. It is sterling Chaplin, existing in its own bubble, unperturbed by encroaching modernity or reality, defiantly without spoken dialogue. That makes it a bit twee, perhaps, but it also makes it endure. Small wonder then, that it ends up on so many “best of all time” lists. It was one of Chaplin’s personal favourites, and Tarkovsky named it as one of his: the only silent film to pass the latter’s exacting standards. Perhaps it’s because it was a silent film by design, rather than by default: the soundtrack is synchronised sound, not written for an orchestra to be performed during the screening, but an integral part of Chaplin’s precise vision. On the other hand, who the heck knows why Tarkovsky likes anything anyway.

Credits and sources:

*All images are screen captures of the film City Lights (1931), and as such are © Roy Export S.A.S., all rights reserved.

**This article owes a great debt to the documentary Unknown Chaplin (1983) by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill. Featuring unique footage from the archive of Oona O’Neil Chaplin, and made with her permission. The entire interview with Virginia Cherrill, from which I quote in this piece, can be seen there, as well as the final scene as it was reshot with Georgia Hale. All three parts of this documentary circulate online, for those who are curious.

Other sources are the usual public ones, as well as Chaplin’s My Autobiography (1964).

2 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #229: City Lights (1931)”