Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

A dark and stirring refrain swells up from the silence, musically suggesting something both epic and haunted. And then a brilliant voice is heard saying the following:

“Long Years Ago, in the Second Age of Middle Earth, the Elven smiths of Eregion forged Rings of Great Power...”

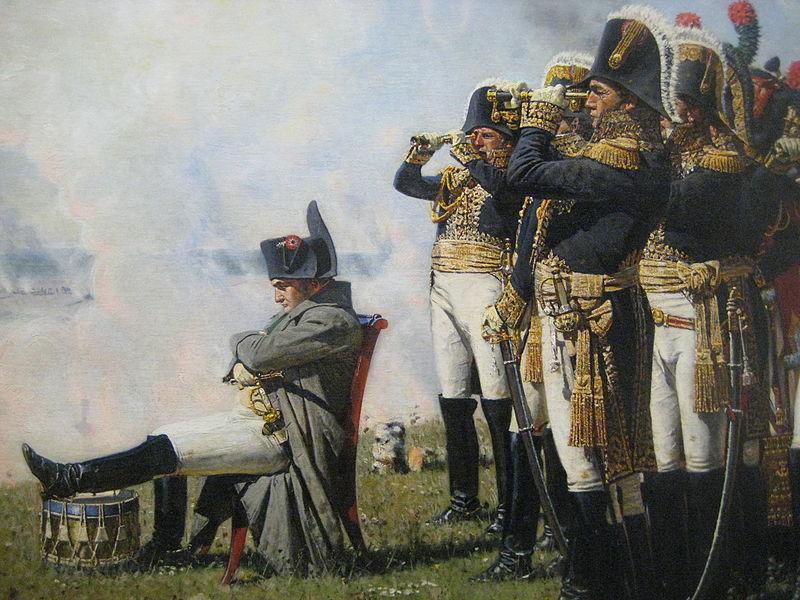

And so begins the BBC Radio version of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord Of The Rings, a thirteen-hour epic that retells all three books. I’ve already talked about the superb cast assembled for this production in a previous Six Damn Fine degrees post, but that’s only one part of this excellent adaptation.

Another is, of course, the scripts themselves. In last week’s column, Julie touched upon the aborted attempt by Boorman to adapt The Lord Of The Rings, an attempt that floundered due to both budgetary issues and how to go about condensing such an epic tale and retelling it in a new format. Boorman wasn’t the only one to fail at this, which is indicative of the challenge posed by this material for adaptors. Attempting this feat for radio were two men: Michael Bakewell and Brian Sibley. The former was a veteran of adapting drama for the BBC TV and Radio who had already successfully brought major established classics from the likes of Tolstoy to the ears of the nation. The latter was a hot new talent at BBC Radio who, when asked what he’d like to adapt, had suggested The Lord Of The Rings. This (not-entirely-serious) ambitious request happened to coincide with the BBC secretly negotiating to get these rights and put Sibley top of the list of the work on the adaptation.

It was Sibley who drew up an episodic structure for the whole adaptation – weaving together the storylines chronologically that are told as separate books in the source text. He drew up a timeline of all the events, and then outlined how this could be told across the planned twenty-six half-hour episodes. Bakewell, the veteran, kindly offered that Sibley take any of those episodes he wanted, and he would do the rest. Bakewell’s experience on BBC Radio’s adaptation War and Peace led to him adapting the battle scenes, while Sibley’s extensive Tolkien research led to him tackling the opening scene setting, adding scenes to help listeners into the world of the story. Despite this division of labour there is such a coherence to the finished work – it all fits together so well.

It was Sibley that determined that the adaptation would need a narrator. And since there was no character from the story present in all the scenes, it would prove very tricky to give one of them this role. So instead the role of the Narrator in this story is one detached from the characters – a omniscient voice able to cover ground from the books that radio drama might struggle with. Gerard Murphy was cast for this role – and he sets the tone so well. There’s an authority to this voice that can cover the hard work of exposition, making it sound important and interesting. But there’s also a warmth: he can subtly fill the gaps when required effortlessly fitting the mood of important dramatic events. A great example of this is how his voice captures the mythical quality required for the opening exposition, before effortlessly switching to a more amiable and engaging register when it comes to introducing us to Mr Bilbo Baggins. I just love the way he makes this switch, and have done since this was the voice that first ever introduced me to the character.

Narrators can be tricky things. With challenging books, a omniscient narrator can become an easy solution to so many problems of dramatising. Too easy, in fact, so that the adaptation becomes a narrated retelling of the story – with a few dramatised interludes. The German radio adaptation Der Herr der Ringe is an interesting take on the tale but as it progresses it becomes ever more reliant on the narrator explaining so much of what is happening that the drama can’t quite take off. It’s one of the great strengths of the BBC version that it skillfully avoids this pitfall – the narration only ever supports the main characters and the action, it doesn’t get in the way by just telling us what they’re doing.

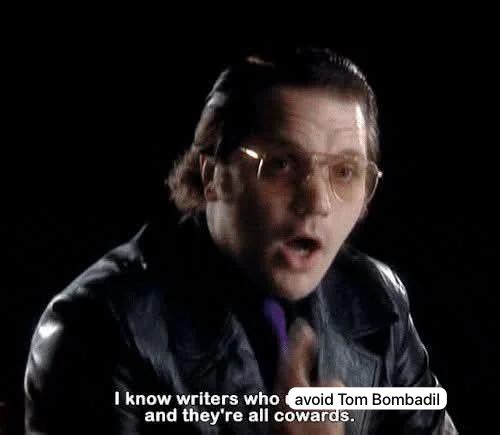

Another feature is that this adaptation – like so many others – misses out Tom Bombadil and the adventuring in the Old Forest. It does leave a gap where these adventures might have taken place – but it does help get the story quickly to Bree. I can understand why adaptations do this. Old Tom, the Old Forest and the Barrow Downs are all elements that Tolkien initially wrote when he still thought he was writing The Hobbit 2. It works in that register: encounters as hobbits are on the way there before they might have to come back again.

By Tolkien’s own admission the story got to Bree, he introduced Strider (for some time a hobbit known as Trotter!) and then felt stuck. He did not know what to do next. And then he linked Strider to the Myths and Legends he’d been working on for decades and the Epic suddenly begins. This adaptation captures that change – there are hints of the epic when Aragorn’s identity is revealed. Suddenly the (surprisingly minimal to this point) soundtrack starts summoning up the fantastical. It’s wonderful stuff.

The adage “the pictures are better on radio” really applies in this instance. It’s a tour de force for the imagination. As a kid I remember listening to it in the evening with all the lights turned off and my eyes closed and really feeling like I was there in Middle Earth. The adaptation achieves this brilliantly mainly thanks to treating every location, every stage in the quest, as something that deserves to be taken seriously on its own terms. It never pretends this is some sort of fantastical pantomime or simplistic twee hobbit tale. The Shire feels real, the scenes here presented with a domestic credibility. But as the characters journey into a world of danger and legend, everything seems to become more epic. The acting becomes more Shakespearean. The change in tone is perfectly handled, taking the listener along with the hobbits into Tolkien’s wider world.

The different locations all take advantage of many different ways in which radio drama works. As the Fellowship journeys through the Mines of Moria the adaptation cribs from all the great suspense dramas like The Man in Black from radio’s Golden Age to become a brilliant exercise in growing audio tension. Bakewell obviously takes all he’s learnt onto the battlefield – and the two great battle sequences manage to feel both operatic in scale but also captures the chaos of it all as events seem to surround the listener.

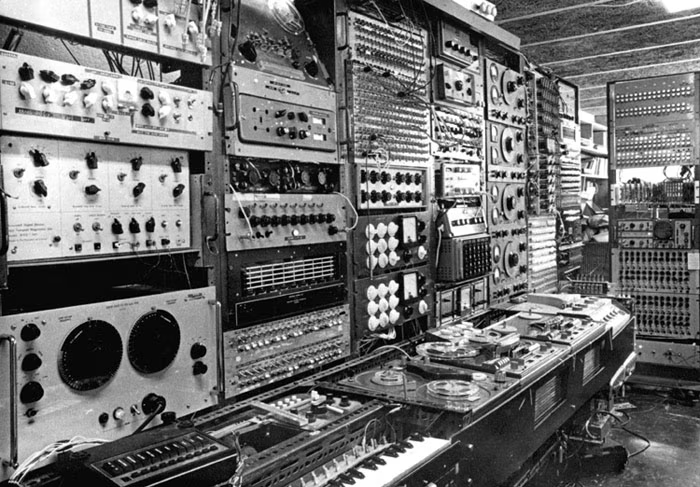

When the story takes us into Lothlorien, the adaptation heads into the sort of world where Radio3 might be dramatizing something far more Spenserian. The music is genuinely, hauntingly beautiful and the voices of the Elven actors deliberately seem detached, capturing this journey into another world. But compared to this stately poetic dramatic style, you have moments like the attack of Shelob which becomes the stuff of avant-garde theatrical nightmares, thanks to the talents of the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop.

All of this might sound disjointed. But it’s the skill of the adaptation that it all fits together so well, as it all becomes all amazing stops along a fabulous journey. Each one interesting in its own right – but fitting within a larger epic. In that sense it captures the spirit of the book. It is a shame, though, that the original version, comprised of twenty-six half-hour episodes, just does not seem to be available anywhere. The subsequent thirteen hour-long episode re-edit is the version that the BBC first released commercially. This is my favourite version, but as a kid we did have half-hour episodes, taped off the radio lying around, and I listened to them so much I still imagine the end music crashing in halfway through of the episodes. I would love to listen to the twenty-six episode version again, but even the Internet Archive has let me down on that score.

There is a more recent re-edit – produced to tie in with the Jackson movies. This cuts the thirteen episodes into the three books, long single adaptations recreating the trilogy as three four-plus hour long dramas. While this is an interesting exercise, I will admit I don’t like these versions. The loss of the episodic format is too keenly felt. And while Brian Sibley got Ian Holm back to record a few brief intros and outros in character as Frodo, these tiny snippets are curios, laden with Tolkien lore and probably quite alienating to anyone not into certain nerdy details about the story such as Frodo’s compilation of the Red Book. My advice is to stick with the thirteen-parter which can still be found online.

There is another factor, alongside the quality of the scripts and the excellent cast, that defines this adaptation to me. It’s as aspect that has left a lasting impression on me, one that stirs with just a few bars of music. It is something that has sent me down many a rabbit hole looking for information (even before the internet was widely available which, let me tell you, is a challenge.) A quest to learn more about a man who helped evoke a love of fantasy in me, and who created sounds that still transport me to Middle Earth. I’m talking about the composer Stephen Oliver. But that, once more, will be another story…