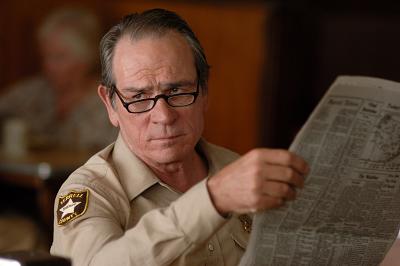

Our summer of collaborations continues with an iconic duo from Minnesota: the Coen Brothers are probably among the filmmakers of recent decades most associated with the (flawed) notion of the auteur – but at the same time, they’re among the directors who keep working with the same collaborators, whether they’re actors (Obviously Frances McDormand, but also Steve Buscemi, John Goodman, John Turturro, George Clooney, and several others), composers (Carter Burwell) or cinematographers (Roger Deakins). In this month’s podcast, we discuss three key films in the Coens’ filmography – Blood Simple (1984), Fargo (1996) and The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) – which all star McDormand and feature soundtracks by Burwell, and we ask ourselves: to what extent are the Coens’ films defined by the brothers’ frequent collaborators? And how much are these collaborators shaped by their work on the Coen Brothers’ films?

Note: Since this podcast was recorded earlier in the summer, we talked about the supposed ‘break-up’ of Joel and Ethan Coen, both of whom have made solo films (The Tragedy of Macbeth and the upcoming Drive-Away Dolls) since their hiatus from one another after 2018’s The Ballad of Buster Scruggs – but they’ve since mentioned in interviews that they are working together on a new film.

For last year’s summer series of podcasts, check this link:

A Damn Fine Cup of Culture: Summer of Directors (2022)

Continue reading