I did it.

I finally finished Augusten Burroughs’ Running With Scissors. And boy, am I glad.

By the time I got to the last chapter, I no longer hated it. I simply didn’t have the stamina for that. I simply found it boring and annoying – and boringly, annoyingly unfunny. There’s little structure in the novel, so the single episodes could all be jumbled up and re-ordered with little to no effect on the book. There’s barely any character development. I’m sure you can write enjoyable novels without character development or structure, but you have to be a hell of a lot better than Burroughs and your story has to be a hell of a lot more interesting. Up to the very end, I felt I was reading the self-indulgent, self-dramatising journal of a drama queen – admittedly one whose childhood and adolescence (as told) were quite horrible, but suffering in itself does not a good novel make.

Anyway, it’s over, and I’ve now started on Haruki Murakami’s short story collection Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman. I recently read his Kafka on the Shore, which was okay but faltered a lot towards the end, and it suffered a lot from having come after The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, which I think is what the Germans surreally call “ein grosser Wurf”. (Roughly translateable as “a great success”; literally, it means “a great throw”, which might make sense if the Germans played baseball.) I enjoyed a lot of Murakami’s earlier short fiction, perhaps mainly because his excursions from the main plot are always fascinating… and in a short story there’s less of a risk that he runs out of steam and the novel peters out. Murakami is a great writer, but endings aren’t his forte.

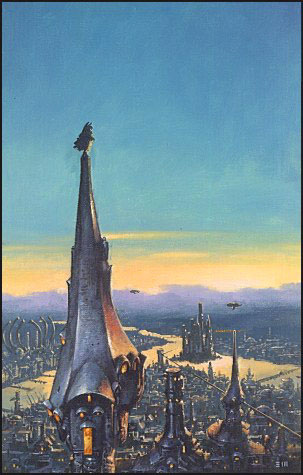

What else? I’ve played on in Anachronox, and it’s as delightfully inventive as I remember. I’ve just left Democratus, one of the great inventions of the game: a planet that makes Switzerland’s political system look positively efficient. On Democratus, every decision requires a vote. Every decision. And every decision has to be discussed in great detail, so that the planet’s High Council even fails to come to a decision about the 64 lethal missiles aimed its way by an aggressive insect race. But watch for yourselves:

Since few of you are likely to still find the game and play it, I’ll go ahead and spoil some of the further plot for you: after you save Democratus, the Council decides to reward you by having the planet shrunk and joining your party. As Wikipedia puts it, “the most annoying civilization in the universe shrinks their planet to five feet in diameter and begins following the team around.” And there’s little as boggling as the sight of that man-sized planet happily floating after you, squabbling about your every decision.