Can one fall in love with a fictional character? More to the point, can one fall in love with a character in interactive fiction, experienced only through (fictional) e-mails? And what if that character turns out to be an Artificial Intelligence?

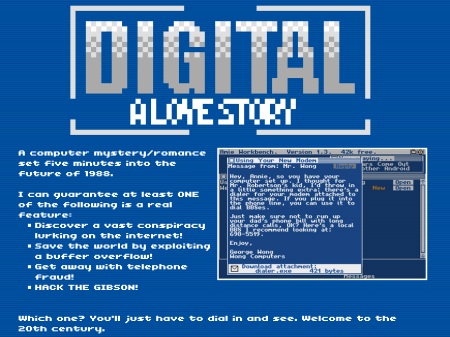

Welcome to the nostalgia soaked world of Digital: A Love Story, an interactive fiction by the improbably named indie game designer Christine Love. Interactive fiction: does that mean Digital is a game? Well, it is, although it lacks many of the conventional traits of games – it cannot be lost, it isn’t difficult as such (there are a handful of puzzles that are well integrated into the plot, but that’s that), in many ways its not all that much more interactive than HTML pages filled with hyperlinks. The notion of an indie interactive fiction, especially one concerned with a theme as weighty and overdone as love, may strike some as pretentious, that most overused and pointless of critical words.

Don’t let any of that keep you away from Digital, though. I’d imagine that Love’s beautiful, intelligent and moving game works best for those who used computers in the late ’80s already and who are at least not completely opposed to the cyberpunk fictions of William Gibson. Digital‘s use of cyberpunk sci-fi is subtle and her interest is always in characters and emotions rather than in technology (at least as anything other than the vehicle for relationships). Her main interest, at least on the basis of this and its successor, the wonderfully titled don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story, is relationships and feelings – though not in a soppy way, as her writing and especially her use of the medium shows her to be eminently smart at what she’s doing.

The whole of Digital happens in the low-tech environment of BBSes or bulletin board systems – basically the pre-internet versions of webpages and message boards. As the player exchanges messages with other users of a number of BBSes, a plot emerges… and a romance develops between yourself, the player, and another user called Emilia. One of Love’s smartest decisions is that the player’s messages are never spelled out. You learn from the replies what you must have said, but the exact words, the details, everything that makes up your personality, is left up to you. It’s this specific kind of gaps in the narrative that is unique to games, pulling you in a way that is very different from how prose fiction engages its readers – and it’s difficult to imagine such compelling experiments in interactive fiction in big-budget mainstream games development. It’s the low-tech environment of indie gaming that makes gems such as Digital feasible.

There’s a twist roughly halfway through Digital, and (perhaps due to half-remembered spoilers in reviews) I’d figured it out fairly early into the game, but it doesn’t matter: Love deftly tells her story with the player’s help in a way that makes it much less about what happens than about how you react emotionally. As Digital came to an end, I found myself sitting there almost crying. A synopsis of the game, even a more detailed retelling, could not evoke the feelings I was going through: it was the sensation that this was my story, that I was living it as it happened, and that it would always be a part of me. Even as I could see the strings by which the puppets were manipulated (me included), there was an emotional reality to Digital that is rare in most fiction, whether interactive or not.

And if I haven’t already turned you off the game, consider this: it’s free. Want to see whether there is anything to my effusive praise? Download Digital here, play it, and then come back and tell me what you thought of it.